Cancel Culture.

This is a general comment about cancel culture after reading Terry Crews's recent tweet.

I agree with some paragraphs, not with others, and will explain some of the concepts/problems related to cancel culture.

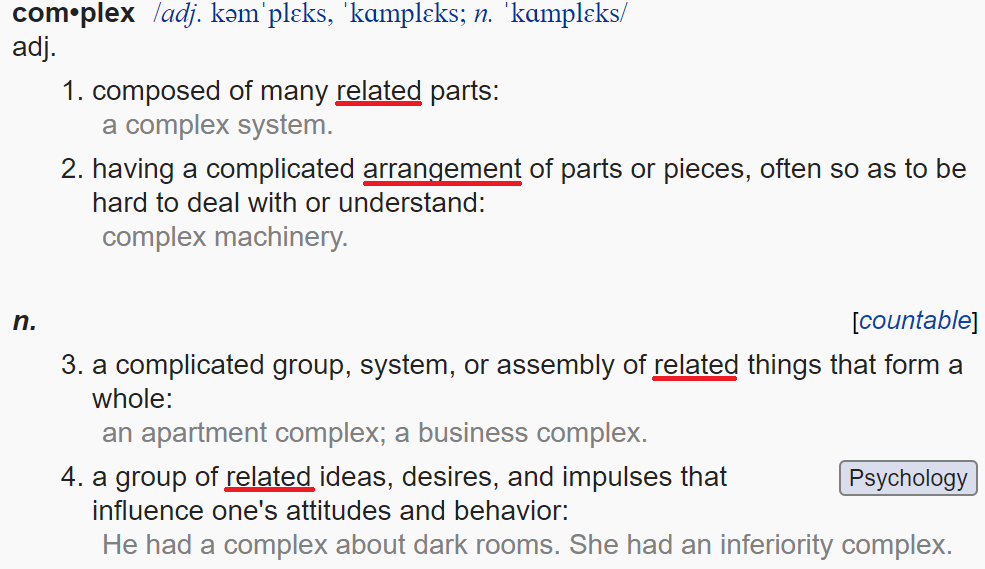

Ambiguous or Unclear Definitions.

To some degree I consider valid the criticism of this term's abuse, precisely because of the lack of an official definition/ambiguity of the definitions.

As you see, different definitions are suggested by people from different fields:

Even if we could discuss about the overlapping, it's obvious that they can be significantly different, leaving too much room for abuse. For example, some people can use the term as reflex because of its negative connotation to instantly reject coherent arguments from a collective.

Also some of the comments under Terry's tweet seem to imply that cancelling only takes place when that person has lost his/her job, influence (would be hard to operationalize), etc., regardless of the intention of the collective.

Fine... We could certainly call cancelling only the result (if it takes place) or use the strictest definition possible to avoid abuse. However, possible systematical social patterns where a group of people misrepresent someone, pretty much dismiss anything positive that person has done in the same social group or the most of it (because of what the group perceives as mistake), even look for old events twisting them to support the new narrative, etc., is still important and worth to be discussed.

As I usually say, you could call tomato or potato culture the social pattern itself and reserve the word cancel for something more drastic, like losing your job; however, you don't need to reach the extreme of losing your job to criticize and analyze the patterns themselves.

The Ratio of Disagreement.

The ratio isn't and shouldn't be considered a good criterion per se.

If you are in a group of 100 people, including yourself, and 99 openly disagree with you, the way they do it and express it is what determines if it's an attempt to cancel you (the social pattern) or not.

Merely disagreeing is obviously not the problem inherently. It could be the origin of a good debate where each side learns something new and/or re-considers own beliefs, or it could be the origin of an attempt to marginalize someone.

Technically, a minority of 40 people could disagree with you and you could still get cancelled if a misrepresentation is strong enough to be spread.

What this means is that you can be cancelled partially even by people who agreed with you/would agree regarding the original topic as well, but still join the other side because of the misrepresentation and the reward of being part of the mob who is right. In the best case, they do know it's a misrepresentation, but just remain silent out of fear, because they don't want to be the next ones.

My point with all this is that we should focus on attitudes, and not so much proportions. Even if there are potential negative effects related to it, like harassment, repetition of points that were addressed many times to exhaust the minority/person that is being cancelled, ease to spread strawman arguments, etc.

Internet.

I have seen some people trying to focus on internet as main factor to explain such patterns, because there isn't a proper selective system to filter non argumented opinions and they will always remain.

I consider this reductive unless it's interpreted as interactive variable with education/personal development. As I have said many times, technology can develop much faster than social norms and we weren't collectively prepared for all the new options that we received thanks to internet.

For example, people in general would like to be heard, receive attention and be valued. But this can have a very negative effect if people aren't educated or stimulated to bring up their opinion only when it's argumented and it provides something of interest/new to the topic. At least to some degree.

Following the analogy from the previous point, 99 people can disagree with you and one or two express the core of the disagreement to have a debate. But if the other 98 just keep repeating superficial interpretations of your stance, misrepresent you, don't listen to your counter-arguments, etc., instead of making interventions when they are well argumented and bring something new to the table, the end result could even be a myth.

You may not know what exactly someone did or said originally and why, or all the relevant circumstances in the original situation, but you may know that said person is considered [insert something negative that ends in -ist or -phobe).

It's frequent to hear expressions like I have heard only bad things about him/her.

But again, note how some will be influenced by this, and others, who developed better critical thinking/skepticism because of different factors, won't. Concluding, again, that internet alone isn't at fault. It's a variable that has negative effects when interacting with other variables.

It's a tool and it's our responsibility to use it correctly (at most apps like Twitter could have a better design to mitigate the effect of said patterns, but they also benefit from such patterns indirectly).

It's a tool and it's our responsibility to use it correctly (at most apps like Twitter could have a better design to mitigate the effect of said patterns, but they also benefit from such patterns indirectly).

Categorization.

Generally speaking, our brain prefers simplicity.

Categorization helps to mitigate the stress of fully understanding any subtle stance from 0, or more subtle than your own current variety of prejudices and categories. It's easier to force a person in a category than trying to understand something more subtle than your own system of boxes to classify individuals, or making a new box for that person.

And even when someone is classified under several categories beyond good/bad, the ultimate integration tends to approach a like/dislike classification in many cases.

Cancel Culture (or the possible negative patterns I described), in this sense, facilitates quick decisions about others and mitigates stress. You don't have to think deeply about some conflict if it looks like Joe or some celebrity is just an homophobe.

And once more... Despite sharing the same design, some people can still overcome such tendency and either remain neutral or do the necessary research to create a more elaborated opinion about Joe or that celebrity.

Again a factor, not the whole cause.

Logical Fallacies.

Logical fallacies are seen as pointless pedantic expressions by some individuals.

And certainly one doesn't need to know their names to identify flawed arguments, however, they are still very common and the terminology helps to describe how communication fails/doesn't progress in debates many times.

- Strawman Argument.

Could be the most common.

People tend to reply to the dumbest version, or at least a much dumber version, of what they originally reply to. When it should be the opposite.

This doesn't mean, however, it's one's responsibility to fix or explain the argument of the other side. An example is:

Men are trash. => Not all men. => I didn't mean literally all men, you idiot.

Regardless of the absurdity of the pragmatic version of all men, to hypothetically encourage the good apples to call out the bad ones (and the ethical inconsistency with other contexts where the same people obviously don't apply it, as there are bad apples in pretty much any big social group and they should say all bus drivers, all nurses, all cricket players, all blacks, all latinos and... all women), it's not our job to distort the original message in the other direction either: make it smarter than what it actually is (let alone when even the smarter version is idiotic).

- Ad Populum.

Despite its simplicity, you can observe with relative frequency expressions like if so many people told you that you are wrong, it's for a good reason.

Lots of people agreeing with you, depending on the situation, may suggest that you are probably right, but it doesn't refute the argument of the counter-part. It can be a mere observation with correlation sometimes, but not an argument per se. We even have hystorical examples where one person or a minority was right, and not the majority.

In the analogy of 1 vs 99, it's still possible that these 99 people are wrong. It doesn't depend on the ratio itself, but the arguments of each part.

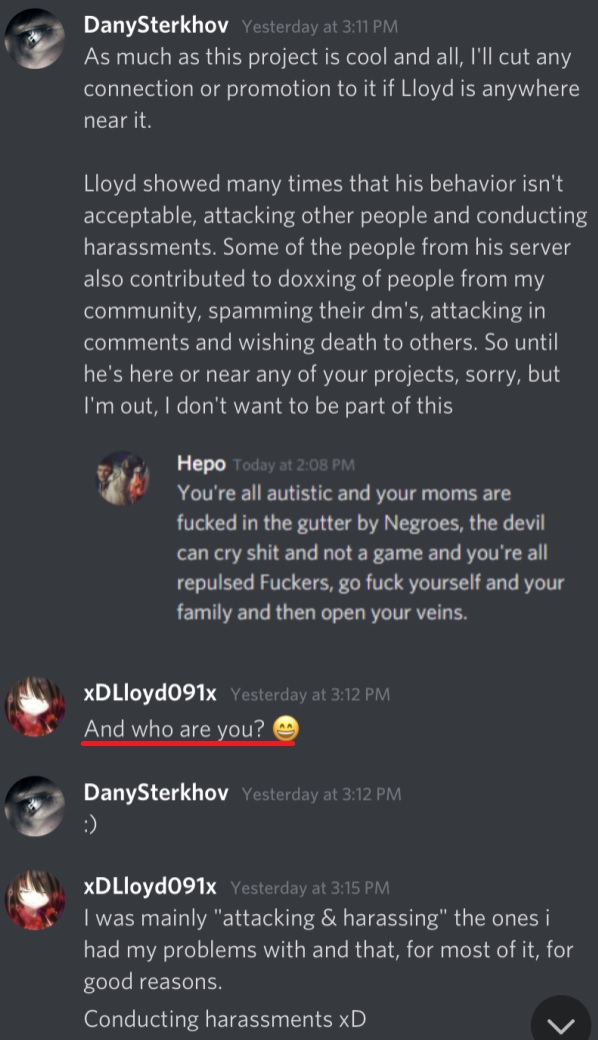

- Ad Hominem.

It's not strictly related to insults (in the popular sense of insult).

Ad hominems are related to an attempt to discredit, talking about the author of the arguments instead of his arguments as core of your counter-argument/refutation. It can be as simple as talking about qualities or even (twisted) past events to make someone look bad instead of properly argumenting in regard to the topic at hand.

Insults or negative comments about someone can be ad hominems as well, but technically, you can even insult someone and still provide non flawed arguments (the insult/observation itself may or may not be wrong).

Insults or negative comments about someone can be ad hominems as well, but technically, you can even insult someone and still provide non flawed arguments (the insult/observation itself may or may not be wrong).

This is why I always say there is a big difference between just insulting and insulting while argumenting (even if it's not the most efficient/best option).

- Circular reasoning.

This person said something racist. > Why? > He said X in this situation. > Why is that racist? I think it's not because A, B, C. > That's just racist.

As idiotic as it sounds, plenty of people fall in this. Instead of addressing A, B, C. Even sometimes being their original statement right (yet not argumented).

Circular reasoning consists in mutually justifying premises or re-using a premise as a conclusion and imply it's an argument. Like:

Someone said something disrespectful because what he said was misogynistic <-> What he said was misogynistic because it was disrespectful.

Someone said something disrespectful because what he said was misogynistic <-> What he said was misogynistic because it was disrespectful.

(Instead of, again, addressing A, B, C).

While in practical examples it's not that obvious because there are superfluous fillers or some steps before going back to the premise, it's sadly common in discussions/debates.

While in practical examples it's not that obvious because there are superfluous fillers or some steps before going back to the premise, it's sadly common in discussions/debates.

This reply from a tweet, for example, boils down to: what you said is homophobic because that's just homophobic.

Possible correct ways to counter-argument...

Regarding natural:

Regarding natural:

Even leaving aside any discussion about how exactly we should define the concept of natural, even if homosexuality was unnatural in the most rudimentary sense, it doesn't imply it's wrong.

Technically not even wearing shoes, playing DMC4 or enjoying a movie is natural.

This logical fallacy is called appeal to nature. Just because something isn't natural, it doesn't mean it's wrong.

Another way to counter-argument is explaining that homosexual behaviors have been observed in other species as well.

Regarding homophobic:

We don't know. Maybe that person didn't think about the counter-argument above and simply questioned homosexuality, which is something that doesn't imply homophobia. As I don't need to hate a conservative person to question his or her beliefs. It depends.

Questioning the status quo is positive. If it has strong arguments to support it, it will stand the questioning anyway; if it doesn't, evolution can happen. But you can't simply expand the meaning of homophobia to saying anything negative about homosexuality.

If that person did hear the counter-argument and doesn't address it, repeats the same over and over with the intention to hurt or mock... Then yes, it's homophobia.

If that person did hear the counter-argument and doesn't address it, repeats the same over and over with the intention to hurt or mock... Then yes, it's homophobia.

The example was utterly simple because with more convoluted ones this would take even longer.

- Appeal to novelty.

Evolution happens in broad terms, but it's not linear. More recent social values, technological inventions or even studies can be more flawed than past ones.

The fact that something is more recent doesn't necessarily mean it's more correct.

Nazism, slavery, etc., were modern at some point, simply because they were recent.

- Burden of Proof related BS.

Burden of proof doesn't mean that you have to stop argumenting just because you didn't start a discussion. Burden of proof is shared as long as you adopt the opposite stance and don't remain neutral.

Proof is also not only empiric evidence. Proof can be an argument that questions the internal logic of a theory, the premises or methodology of a study, etc.

Burden of proof in law =/= Burden of proof in science/philosophy.

- Appeal to authority.

Another one that should be pretty simple, yet it's commonly used.

Just because of someone's reputation, degree, profession, etc., we can't conclude logically that the person is necessarily right. We can decide to listen more carefully to X person because of said reputation and qualities, but it doesn't mean the arguments themselves are necessarily right (or wrong).

Just because of someone's reputation, degree, profession, etc., we can't conclude logically that the person is necessarily right. We can decide to listen more carefully to X person because of said reputation and qualities, but it doesn't mean the arguments themselves are necessarily right (or wrong).

These are some of the many forms many people demonstrate they don't know how to argument or counter-argument.

And it's one of the biggest factors in the over mentioned patterns.

What's an argument?

Argument should be a piece of information composed of premises and a conclusion that should logically derive from the premises themselves. Sometimes the premises are implicit and it's required to state them explicitly to make the argument more clear (or how flawed it is...).

What's a counter-argument?

A counter-argument is a piece of information that attacks:

1) The premises of an argument;

1) The premises of an argument;

2) And/or the logical relation between the premises and the conclusion.

Education would play a big role if subjects like philosophy (especially epistemology, logic and ethics) and psychology were implemented from basic education. Understanding how prejudices work, confirmation bias, etc.; along with logical fallacies, ethical consistency, construction of knowledge...; would prepare individuals with better tools to communicate and discuss.

But nowadays we live in an era where many think they have something valuable to say and give lessons, while not even understanding what an argument/counter-argument means.

This is not to say I have never done mistakes myself and have never fallen in some logical fallacy/flawed argument. I definitely have, but I knew how to identify them, dissect and re-adjust.

False Positives and True Positives.

All these points don't imply true homophobes, racists, transphobes, misogynists, xenophobes don't exist.

It's perfectly possible that in the original 1 vs 99, that 1 is really wrong and falls in one of the categories above.

It's perfectly possible that in the original 1 vs 99, that 1 is really wrong and falls in one of the categories above.

The problem is that many false positives will be generated just from the way Cancel Culture (or potato culture) supposedly works.

And finally, the most productive way to handle a true positive isn't necessarily trying to isolate that person and hating for life. Let alone exaggerating or distorting the mistake itself.

Obviously it's not the same to rectify vs repeating the same mistake over and over, in which case isolation/separation may be beneficial for boths parts. But one has to make sure that there was no other choice first (before urging a big crowd to dismiss another human being).

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario