The “Style/Fun is Subjective" cliché (unfinished+Notes).

I won't keep and use this like a blog in a traditional way. This is just more comfortable than sharing files.

I started writing a text some time ago to counter argument a few clichés against the implementation of inertia in DMC5, but it lost quickly its purpose.

To not throw it in the waste bin, I tried to transform it in something else, and my intention was to explain:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Objectivity has mainly 2 definitions:

I started writing a text some time ago to counter argument a few clichés against the implementation of inertia in DMC5, but it lost quickly its purpose.

To not throw it in the waste bin, I tried to transform it in something else, and my intention was to explain:

- Why we play video games.

- Why complexity is correlated to fun in DMC and video games (one can have fun with simple games, but, in terms of probability, for shorter periods of time and with a less intense reward, which I wanted to explain as well).

- Misconceptions about subjectivity and style (or perception of beauty in DMC or other videogames).

- Why we get bored from video games.

And more.

For now it's unfinished, unpolished, unorganized, I may delete some superfluous parts (I considered explaining some things in different ways and with different examples), etc. I may update it or I may leave it like this out of laziness and the high probability that pretty much nobody will read it.

The purpose of the topic about subjectivity/objectivity is not to imply it's possible, let alone that we should establish any kind of precise, unequivocal hierarchy among players, but rather to explain the possibility of identifying relevant variables (you would understand this much better after reading).

I already know it's very long. Don't ask me for TL;DR versions.

The purpose of the topic about subjectivity/objectivity is not to imply it's possible, let alone that we should establish any kind of precise, unequivocal hierarchy among players, but rather to explain the possibility of identifying relevant variables (you would understand this much better after reading).

I already know it's very long. Don't ask me for TL;DR versions.

And if you don't like the way I express anything or see some mistake, feel free to suggest improvements, unless you are too lazy for it.

(That's it for now).

(That's it for now).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

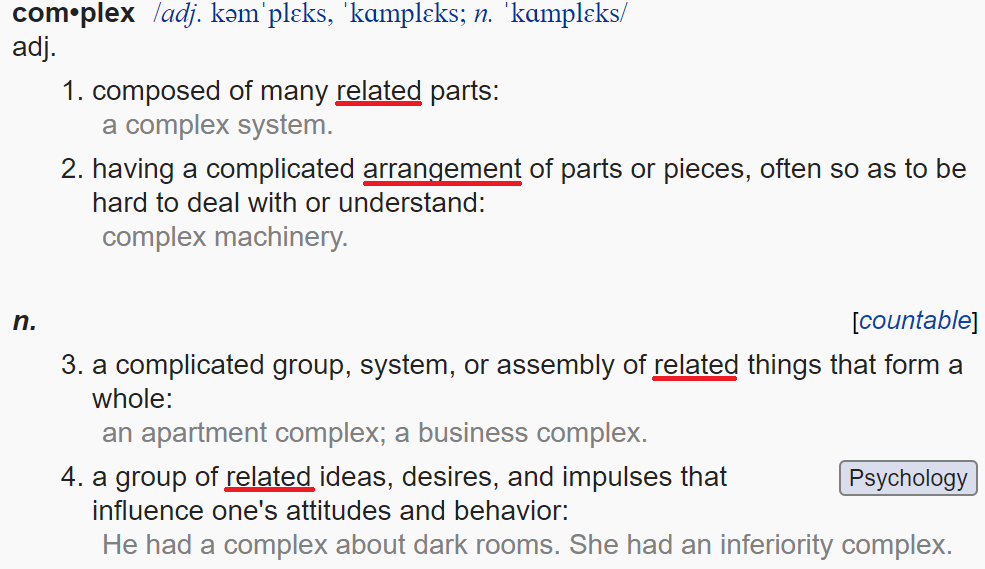

Objectivity has mainly 2 definitions:

The first one has to

do with the existence and conditions of X object or portion of the reality, regardless of our perception

or symbolic representation of X. Originated mainly from

philosophy.

The second

one (not totally

independent from the first one) is related

to impartiality, and useful in the contexts of,

for example, journalism and science:

how affected are our criteria and acts by

certain variables and conditions exclusive to us (experience, beliefs, etc.),

compared to another person.

However, by

default everything is perceptive, since we

cannot NOT perceive from another

reference than our own design and perception, let alone an omniscient

creature able to see every single bit of the reality "as it is" (assuming such a simple concept would be valid).

Even science

is subordinate to epistemology,

which is a branch of philosophy focused on the elaboration of the

best strategies to build knowledge (including the scientific method).

These strategies are not objectively perfect. It's a mere

process of optimization contrasting the consistency and coherence of

different strategies and methods applied in an open system; in opposition to formal science and closed systems like formal logic, mathematics or a

game like chess.

Which is why in an irregular (but constant in the long term) progress and approach to more and more consistent knowledge, scientific conclusions from studies and even entire scientific theories have been reformulated and reinterpreted during centuries. Some were even considered paradigms in their time, and in a similar way we consider generally accepted many theories, which will most probably get redefined or improved in some future.

Which is why in an irregular (but constant in the long term) progress and approach to more and more consistent knowledge, scientific conclusions from studies and even entire scientific theories have been reformulated and reinterpreted during centuries. Some were even considered paradigms in their time, and in a similar way we consider generally accepted many theories, which will most probably get redefined or improved in some future.

We could say:

epistemology and science

increase systematically and progressively the probability to be

interpreting reality as it is (objectively:

first definition), while minimizing the

influence of individual variables while studying it (objectively:

second definition).

But in the moment one

considers:

- Everything must be objective in some way. Even perception exists as a synaptic combination that could be even mathematically represented if we knew exactly how it works, and obviously also as our psychological reality;and...

- We could want to study any object, as object of study. This includes us: precisely the way we perceive things, and why.

It's

clear that the dichotomy subjective/objective is not really useful

terminologically in the most of the practical contexts.

For example, the

taste of an apple is related to

chemical variables in the apple, the chemical receptors in the tester's tongue, the overall transduction in our central

nervous system and, then, extraneous variables like the perception of the

origin of the apple, the presentation of the apple, our mood when

eating it, where we eat it, with whom, etc.

The point here is

that everything is about either relevant

variables related to a concrete

topic/object of study or (presumably) irrelevant

ones. Not this

is subjective, so it doesn't count, analogous to it's magic,

whenever

you actually lack arguments (not saying it's always used in such

scenario).

Even the perception

of beauty, individual or analyzed in terms

of patterns, is a synaptic combination that

IS part of the reality, and is related to external variables like

symmetry, social cannons, the interaction with the perceived

"object"/person, etc. It's not an abstract magical nebula

in our mind that can't be analyzed and structured in more or less

relevant variables depending on what we

want to study from it. Everything

is about dependent and independent variables that interact in

different and complex ways.

If we were talking

about the functionality

of katana's move set patterns in videogames vs long swords, variables

like "having watched the 7 Samurai or not", "having

watched Kenshin or not", etc., when growing up, would be

obviously irrelevant, affecting our

aesthetic preference. In such case, if both move-sets were equally

complex and with parallel functions,

I would say that katanas are only a "personal preference",

and not because of functionality.

But this doesn't mean any discussion about

which weapon one prefers is actually pointless because this "taste" is "subjective" per se. It simply means there aren't current

relevant variables in the debate keeping in mind the object of

discussion. THIS is why it would be pointless, not because "it's

subjective".

In the same way we

can, for example, analyze the

integration of a mechanic such as inertia and distinguish what is an aesthetic preference and what is relevant

for the variables we are interested in (like style or fun).

If we had a game where you

could only swing one weapon with a predetermined move-set, without

any variation, without juggles or anything else, we could set it as

base. Probably nobody would consider it interesting. And only stylish

because of irrelevant variables depending on the weapon and personal

preferences about aesthetics.

Now imagine that we add

the ability to jump and do one aerial sequence similar to the ground

sequence we had already in our "base game". We would agree

that it's a small improvement, right? Even if minuscule.

Progressively we can add a

launcher and "self-launcher", another weapon, mechanics to

cancel and a long etc. of more and more options (assuming they

complement and interact with each other in a non-superfluous way).

Can you imagine a single

person that would say the end-product has less stylish potential

than the base game?

No.

But why? Wasn't style subjective...?... What happened? It would be too much of a coincidence that many people developed their "subjective perception" to come to the same conclusion about something "subjective".

But why? Wasn't style subjective...?... What happened? It would be too much of a coincidence that many people developed their "subjective perception" to come to the same conclusion about something "subjective".

In the same way

pretty much nobody would find more stylish a few ground combos with

DMC4 Dante compared to gameplay that integrates different advanced

techs in harmonic order and different types of movement in the air.

You can say that

these are some exaggerated examples, however, they are better to

illustrate the overlapping among different observers and general

patterns in the perception of "style".

Yes, 2 observers can

still differ in a discussion about who is more stylish when comparing

2 high-level DMC players. But this happens mostly because of irrelevant variables for the

topic, similar to the simplistic examples above with films, anime

and, in general, exposure to different stimuli in our life time that

consequently make each observer develop a unique aesthetic taste and

unique perception. Let alone other types of bias related to personal considerations about the player and more.

This doesn't change the fact that there are general patterns in our design, in this case our perception, that explain why that "raw base game" mentioned above will have less stylish potential, or why a noob player will be perceived as "less stylish" commonly, regardless of the less relevant variables.

This doesn't change the fact that there are general patterns in our design, in this case our perception, that explain why that "raw base game" mentioned above will have less stylish potential, or why a noob player will be perceived as "less stylish" commonly, regardless of the less relevant variables.

The individual human perception of each observer is unique because each

one of us is a unique combination of genes that has interacted with a

unique sequence of stimuli, but our brains and general design

obviously still follow common rules, establishing patterns and

tendencies. It has been studied in different disciplines and saying "style is subjective" in any discussion is as bland as saying "beauty is subjective", so let's ignore the fact that our

perception clearly tends to favor, for example, symmetry.

Complexity

and variety

are 2 of the most relevant variables that influence the variables we

are focused on: style (potential

to be perceived as stylish) and fun.

To understand better

why these variables are relevant, one should first have (at least) a

notion about habituation

(not its popular definition, but the one related to psychology), and

secondly, our goal-oriented

design.

Habituation

is a basic and pretty universal learning process, where the response

of an organism, when being exposed to certain stimuli under the same

circumstances, is progressively less intense. In humans' case it

interacts

in a much more complex way with other processes and it's also related

to the feeling of boredom.

A primitive and

basic example would be your reaction when you hear repeatedly a loud

noise in a context where you shouldn't, and without further or

different consequences. The first time you would be surprised, maybe

even scared; your organism would prepare yourself

for the unexpected. The second time, your response would be probably

less intense... And after 50 repetitions, you wouldn't be surprised

or scared at all (assuming there is no

sensibilization from overthinking, deep introspection focused on the

stimuli, let alone paranoia). It would

merely be an annoying noise; a stimuli

you should not care

about.

The function of

habituation is very complex in our case, since

it interacts with other processes, but

without going in depth, we could say:

1) It helps to discard

irrelevant and old stimuli from new ones. This helps to focus our

attention (our operative memory is limited) and sources on what is

(on paper) relevant and deserves any adaptation and energetic investment.

2) It stimulates the

search for new stimuli. We can't be satisfied and happy doing exactly

the same over and over without either variety

or breaks (lapse

of time between stimuli is one of the variables that can affect the

probability to react again intensively). This augments the tendency

to keep moving and seeking for new social interactions, sexual

partners, basic stimuli like types of food or any activity that could

be pleasant or satisfying.

Which is, in the end, a tendency to improve our situation and

conditions.

Obviously, the more

relevant function or aspect for the topic is the second one, and

interacts with goal-orientation.

Goal-orientation:

We feel good

relativizing between different states and our happiness depends on

it. This is why we can't be "happy" for a long term simply

satisfying our necessities in a regular and non-challenging way

(food, sleep, social interactions, sex and even love). The following

examples are significant tendencies

and

patterns (of course you will find exceptions, since there are many

relevant variables interacting depending on the context):

You have to feel a bit

alone to miss somebody, and then, when you finally establish a

complex relationship or interaction, feel the proper and intense

pleasure from social interactions; you have to be at least a bit

hungry to feel properly the pleasure of eating a tasty food; you have

to lack at least for a while sexual stimulation to feel... You get

it, do you?

We are designed to feel

great in a constant process of relativization,

overcoming difficulties and negative situations to achieve an

improvement. Including the most of the learning processes. You

learn something new, and depending on its complexity, how useful it's

for further objectives, etc., you will feel good/better than before

starting the learning process. (This is why

complexity

is a relevant variable for fun,

but we will get back to this later).

After this very

general explanation of our goal-oriented design, we have to take into

account that our brain evolved in a very

different context, and science, technology, social transformation

develop faster.

In the

current state of human civilization

(western society) we are getting an overexposure to many stimuli. We

have pretty much always food at "reach", sexual stimuli, the

chance for quick social interactions, etc.; and most difficulties are

too trivial to maintain a healthy relativization and challenge-reward

cycle.

This is why hobbies exist.

They are artificially designed difficulties in an controlled

environment that compensate the lack of natural challenging

difficulties that would keep us

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario